Who Really Controls Your AI?

Inside the Global Struggle for AI Sovereignty. And Why Infrastructure, Regulation, and Geopolitics Are Defining the Future of Power

Introduction: What’s Really at Stake

The world is undergoing a structural shift in how power is wielded and maintained. Once dominated by diplomatic pacts, institutional multilateralism, and economic interdependence, the current international order is fragmenting into techno-political blocs. At the heart of this transformation lies a simple but powerful concept: control over digital infrastructure. And within that infrastructure, artificial intelligence has become the new ground zero.

Read further about TechnoPolitics below:

“Power politics has migrated from chancelleries to chip fabs and cloud regions.” Technopolitics: A C-Suite Playbook

Or listen to my latest interview on AsiaPulse:

AI sovereignty refers to the ability of a state (or an enterprise) to develop, deploy, and regulate artificial intelligence systems without dependence on foreign-controlled infrastructure, data, or algorithms. In an era where machine learning powers not only consumer apps but also healthcare diagnostics, military targeting, supply chain optimisation, and financial decision-making, the stakes of dependency are existential.

AI is not unlike the fight for control over the semiconductors, well documented by Chris Miller in his book: Chip War. With the risk of oversimplifying the book a bit, here are the key learnings I have retained:

A Silicon valley based innovation (giving it its name!)

A demand for semiconductors initially heavily driven by the Pentagon for military applications (guided missile systems) and by the Vietnam war - later on by civilian applications such as radio receivers, hearing aids, calculators, etc.

An asia centric production process early on, with manufacturing centers across Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea and Japan to keep the cost low and build scale

A geopolitical agenda: Asian nations wanted American interests on their soil to ensure they will get military protection especially after the Vietnam war was lost and the US foreign policy in Asia was unclear: eg. “The US might not care about Taiwan but they will care about Texas Instruments!”… it was in 1969. And the same phrase remains true about TSMC today. At the same time the US saw this commercial expansion as a way to fight the influence of communism with soft power; as these intertwined economic interests will create a techno-political power block.

A dramatic turn of events: when Japan started to dominate the semiconductor industry globally in late 1980s with high quality, low costs products, and innovation (Sony’s Walkman launched in 1979); Silicon Valley started lobbying the US government to fight back trade agreements (export quotas, anti-dumping measures, market access, tariffs, …), legal actions (Intellectual Property lawsuits) and subsidies (SEMATECH). This, combined with the appreciation of the Japanese Yen due to the Plaza Accord and the rise of South Korea and Taiwan as semiconductor manufacturers, contributed to a decline in Japan's market share and a period of stagnation for its semiconductor industry.

It’s easy to draw a parallel with the above; however the challenge is even greater today as the value chain is even more integrated than it was before.

And similarly, today the digital environment is increasingly shaped by coercive tools such as export controls, sanctions, and extraterritorial laws like the U.S. CLOUD Act, leaders in both the public and private sectors are beginning to realize that what was once considered global and open is now fragmented and conditional.

1. The Geopolitical Landscape: The Three Power Blocs

For the purse of this article, I am focusing on the three main power blocks: USA, China and Europe. But we do need to recognize the growing influence of the Middle East (UAE’s Stargate investment and Saudi Arabia’s Humain) and the Global South who will drive both demand and new innovations due to localization needs.

The United States: Deregulation + Infrastructure Dominance

Under the Trump II administration, the U.S. is pursuing an aggressive AI industrial strategy. The $500 billion public-private initiative known as Stargate USA is designed to secure American dominance across the AI value chain; from chip design to cloud hosting to frontier model development. This plan is complemented by relaxed export controls on advanced chips and a 10-year federal moratorium on state-level AI regulations.

Through strategic partnerships in the Gulf and selective licensing of advanced GPU access, the U.S. aims to maintain global supremacy in AI infrastructure while projecting influence over allies' digital policies.

China: State Control and Technical Resilience

China, by contrast, is doubling down on its model of state-led development. The government spends approximately $25 billion annually on chip research and has enacted strict AI regulations that require all generative models to undergo government review before deployment. In response to U.S. sanctions, Chinese researchers are advancing techniques like mixture-of-experts to train high-performance models using far fewer compute resources.

China is also investing in universities and startups to create "controllable AI"; that is, AI that aligns with state ideology and cannot be co-opted by foreign adversaries.

The European Union: Rules Without Infrastructure

Europe’s strategy is fundamentally regulatory. The AI Act aims to set global standards for trustworthy AI through a tiered risk-based framework. While this approach leads in ethics and compliance, it remains weak in industrial autonomy.

Initiatives like InvestAI (a €200 billion investment program) and Gaia-X reflect attempts to regain digital sovereignty (a Euro Stack), but Europe remains highly dependent on American cloud services, chips, and AI platforms. In France, Mistral AI is working with Nvidia to build an end-to-end cloud platform powered by 18,000 Nvidia Grace Blackwell systems underscores this reliance.

Europe is positioning itself as the world's digital referee; without yet building the infrastructure to host the game (!).

2. The AI Value Chain: Concentrated, Vulnerable, and Geopolitically Exposed

To understand AI sovereignty, we must first map the full value chain of artificial intelligence. Each layer, from raw materials to application interfaces, presents its own dependencies and vulnerabilities.

The artificial intelligence value chain is built upon a highly resource-intensive and dangerously concentrated foundation. Each layer of the AI pipeline, from physical components to data and software, is controlled by a small number of actors, many of whom are concentrated within specific geopolitical blocs. This concentration introduces systemic risks, from supply chain disruptions to unilateral regulatory interventions.

Water

At the upstream end, chip manufacturing relies heavily on the consumption of critical physical resources. Producing a single computer chip requires between eight and ten gallons of water, and cooling a data center can demand up to 300,000 gallons of water daily. These demands pose a risk in drought-prone regions or where water access is politically controlled (Lenovo News).

Energy

The energy burden is equally substantial. The International Energy Agency projects that global electricity consumption by data centers will double by 2030, largely driven by the training and deployment of AI models (IEA).

Further reading: my extensive report on AI & Energy below in collaboration with ENSSO, Geneva-based Energy consulting firm.

Rare Earth Minerals

Control over rare earth minerals, essential for semiconductor production, further exacerbates geopolitical vulnerability. China processes more than 80% of the world’s rare earth minerals, giving it disproportionate leverage over the upstream supply of components essential to AI hardware.

Lithography Systems

When it comes to lithography systems, the machines used to etch circuits onto silicon wafers, one company, ASML, holds a near-total monopoly. It commands nearly 100% of the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography market and about 90% of the deep ultraviolet (DUV) systems segment.

Chip Manufacturing

Downstream, chip fabrication is equally centralized. Taiwan’s TSMC alone accounts for over 90% of the global production of 3nm and 5nm chips and controls 62% of the total foundry market. Any disruption in Taiwan, whether due to natural disasters or geopolitical conflict, would pose a catastrophic risk to global AI capacity.

GPU

In the GPU segment, essential for AI training and inference, NVIDIA dominates with more than 80% market share (Morningstar).

Network & Communications Fabric

The infrastructure that moves and processes AI data, networks, satellites, 5G equipment, and submarine cables, is managed by a handful of corporations including Google, Meta, Huawei, Starlink, Alcatel, Ericsson, and Nokia (Maximize Market Research).

Data Centers & Cloud Infrastructure

Cloud infrastructure is another point of concentration. The top three providers, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform (GCP), control over 66% of the global market (Statista).

The U.S. also dominates the global data center landscape, hosting over 5,400 facilities. This accounts for 45.6% of the world’s total and is nearly ten times the number found in Germany, the second-ranking country (Visual Capitalist).

Training Data

Data used to train large language models (LLMs) also suffers from a lack of diversity and transparency. Approximately 60% of training datasets come from Common Crawl, with the remainder drawn from books, Wikipedia, academic publications, and source code repositories. Many of these datasets are not legally licensed, raising ethical and legal concerns (Common Crawl). You can see here a list of 39 pending copyrights law suits in the US.

Foundation Models

In terms of model development, the imbalance is stark. Ninety-four percent of the world’s most powerful foundation models are either created in the U.S. or controlled by U.S.-based entities (Polaris Market Research).

And more, most of these companies such Open AI, Anthropic, xAI, Meta, are dominated by controversial, unchallenged founders with little oversight and weak governance on their board. As LLMs are becoming foundational to many AI applications and for decision support; it gives them monumental ‘editorial rights’ over the content generated by these models: from the selection of data used for training to defining what’s a good or bad output; their influence over the AI generated content (already pervasive across social media and businesses) is immense.

To illustrate my point, see the post below from Elon Musk: what gives him the rights to rewrite the corpus of human knowledge and add / delete “errors”? Who defines what’s missing or what’s an error? Again, let’s remember that this technology is now powering autonomous robots, enterprise applications, social media content, …

Applications

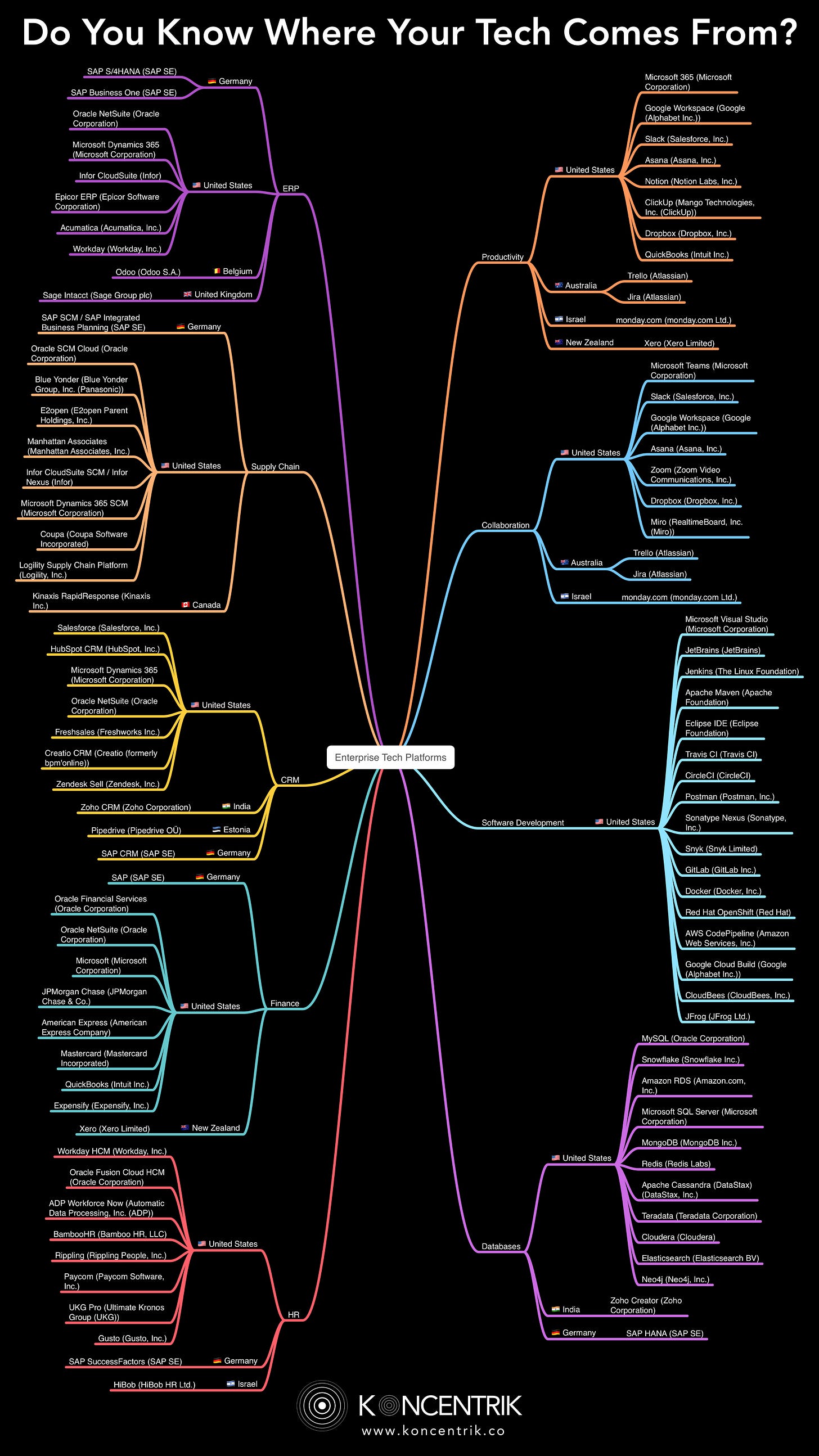

Finally, enterprise applications, the interface through which AI often delivers value, are overwhelmingly U.S.-based. In 2024, Oracle surpassed SAP as the leading global ERP vendor for the first time since 1980. Today, 85% of the most widely used enterprise applications originate from U.S. firms (Coherent Market Insights).

Below are ~ 100 tech platforms mapped by category and country of origin.

This extreme concentration across all layers creates systemic exposure: a single legal change in Washington, a semiconductor embargo from Tokyo, or a data localization law in Brussels can paralyze parts of your AI stack overnight.

3. Case Studies: Who Got Caught in the Crossfire?

AI sovereignty is already a lived reality for several organizations and governments that have found themselves exposed to extraterritorial regulations, shifting political alliances, or geopolitical weaponization of technology.

Below, we examine a selection of cases that highlight how fragile digital autonomy has become in a fragmented world.

Case 1: NVIDIA’s China Chip Challenge

In 2023, the U.S. Commerce Department issued a new round of export controls banning the sale of high-end GPUs, such as Nvidia’s A100 and H100, to China. These GPUs are essential for training and deploying advanced AI models, particularly in data centers and enterprise AI labs.

Nvidia responded by developing slower, customized versions of its chips to comply with U.S. restrictions. However, this workaround was insufficient. By early 2025, the company had written off $4.5 billion in revenue due to reduced access to the Chinese market. Its share of China’s data center GPU segment dropped from 95% to approximately 50% within 18 months, as Chinese firms like Huawei and SMIC rapidly advanced domestic alternatives (CNN Business).

This case underscores how geopolitical decisions in Washington can reshape global supply chains and accelerate technological decoupling.

Case 2: Doctolib and the AWS Data Sovereignty Ruling

Doctolib, a French healthcare platform used by millions, faced legal scrutiny when it relied on Amazon Web Services for cloud hosting. The issue arose from the potential that U.S. law enforcement, under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Section 702, could subpoena data stored even in European AWS data centers.

In a landmark ruling, France’s Conseil d’État required that any healthcare data hosted by U.S.-linked cloud providers be protected by additional technical and organizational safeguards. The compliance costs across the French tech ecosystem exceeded €120 million as firms scrambled to implement encryption, key management, and alternative hosting solutions.

This case established the now-widespread concept of “data sovereignty by association,” where proximity to U.S. infrastructure becomes a regulatory liability within the EU.

Case 3: ChatGPT’s Temporary Ban in Italy

In March 2023, the Italian data protection authority (Garante) temporarily banned ChatGPT, citing concerns over data processing practices and the absence of age verification measures. OpenAI was forced to suspend operations in Italy for over a month while it implemented local compliance procedures.

Although the ban was lifted after changes were made, the case prompted a broader conversation about the responsibilities of AI service providers under GDPR. It also served as a catalyst for the EU’s AI Act enforcement mechanisms, signaling that regulatory bodies would not hesitate to suspend access to powerful models if they violated local rules.

The episode revealed how AI services could be instantly disabled, even in advanced markets, over legal ambiguities, an operational and reputational risk for any company deploying frontier models.

Case 4: Stability AI and Open-Source Tensions in the EU

Stability AI, the company behind open-source models like Stable Diffusion, found itself under intense regulatory pressure in 2024. Although celebrated for democratizing generative AI, the firm faced growing scrutiny from EU regulators under the draft AI Act for issues related to model traceability, bias mitigation, and post-deployment monitoring obligations.

Faced with mounting compliance costs, Stability AI scaled back its European operations and shifted focus to more permissive jurisdictions. This had a chilling effect on other open-source initiatives in the region, as startups realized they might not be able to meet the obligations placed on so-called “general-purpose AI systems” (source).

This case illustrates how regulations, however well-intentioned, can inadvertently entrench incumbents while discouraging innovation in open ecosystems.

Case 5: Google DeepMind and NHS Data Controversy

In a now-infamous episode, DeepMind and Google were found to have used the personal health data of 1.6 million NHS patients in the UK without explicit consent. Although the partnership aimed to develop AI-powered diagnostics, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office ruled that the agreement violated privacy laws and failed to meet standards of informed consent.

The backlash forced the implementation of stronger transparency mechanisms and audit requirements for health data used in AI training. It also highlighted how opaque data practices, especially by U.S.-based firms, can provoke public and legal backlash in regions with strong data protection regimes.

4. Case Studies: Who Is Regaining Control and How?

Despite the challenges, several companies and national initiatives are pioneering pathways toward digital sovereignty. These examples show that regaining control over AI stacks is possible, albeit complex, costly, and geopolitically sensitive.

Case 1: JPMorgan Chase’s Internal LLM Suite

As one of the world’s largest financial institutions, JPMorgan Chase opted to develop its own large language models internally rather than rely on API access from OpenAI or other third-party providers. In doing so, the bank aims to protect sensitive financial data, ensure compliance with SEC and banking regulations, and retain full ownership over model outputs and logic (CNBC).

This strategic decision reflects a broader trend in the financial services industry, where concerns over data leakage, model hallucination, and regulatory unpredictability are driving a shift toward in-house AI capability building.

Case 2: Switzerland’s Sovereign AI Stack via Kvant

The Swiss government-backed initiative Kvant AI exemplifies how smaller nations can achieve sovereignty through partnerships and legal architecture. By combining IBM WatsonX with Phoenix Technologies’ Swiss-based cloud infrastructure, the initiative allows for sovereign AI development fully under Swiss jurisdiction.

This hybrid ecosystem aligns with Switzerland’s long-standing traditions of neutrality, privacy, and decentralized governance, demonstrating that sovereignty can be achieved without scale, as long as there is institutional coherence and local infrastructure.

Case 3: India’s Sarvam AI and the Atmanirbhar Bharat Strategy

India’s Ministry of Electronics and IT has designated Sarvam AI to lead its development of Indic-language foundation models. This effort not only addresses cultural representation gaps in major LLMs but also aims to prevent the export of sensitive training data to foreign jurisdictions.

Part of the broader “Atmanirbhar Bharat” (Self-Reliant India) vision, this initiative illustrates how large, multilingual democracies can drive AI development aligned with national values, legal norms, and infrastructure sovereignty.

Case 4: G42 and Strategic Realignment in the UAE

Initially reliant on U.S. firms like OpenAI and Nvidia, G42, the UAE’s flagship AI company, is now developing a 5-gigawatt AI campus to anchor its compute and hosting capabilities. It has also restructured its partnerships to align more closely with U.S. political expectations, demonstrating the geopolitical negotiation required to gain access to premium AI technology.

While this may be a form of "aligned sovereignty" rather than pure independence, it offers a useful model for resource-rich states navigating between great power blocs.

Case 5: DeepSeek’s Cost-Efficient Innovation in China

Facing chip embargoes and export controls, China’s DeepSeek project produced an open-weight Mixture-of-Experts model for under $6 million, roughly one-tenth the cost of GPT-4-scale projects. By leveraging sparse activation and efficiency-driven architecture, DeepSeek shows that innovation can partially offset infrastructure disadvantage.

This case emphasizes that sovereignty is not just a matter of policy or geography, it can also emerge from architectural ingenuity and computational frugality.

Case 6: Volkswagen Group and Industrial AI Sovereignty

Volkswagen’s internal AI Lab is pioneering sovereign platforms for autonomous driving and industrial automation. The company has built a proprietary data layer known as GAIA and is developing end-to-end AI systems for safety-critical environments, entirely under German jurisdiction (IoT World Today).

By embedding sovereignty into vertical integration, Volkswagen ensures alignment with European regulatory frameworks while protecting IP and model integrity.

5. Mitigating Sovereignty Risk: A Four-Pillar Playbook

Enterprises that rely on advanced AI must confront a fundamental question: What would happen if a key part of your AI stack became unavailable due to regulation, sanctions, or political instability?

The path toward AI sovereignty is not binary as full independence may be impractical, but strategic autonomy is both feasible and necessary.

This section proposes a practical framework, organized around four pillars: infrastructure, data, models, and applications.

Infrastructure

The physical and virtual backbone of AI, including cloud platforms, compute clusters, and network topology, is the most immediate point of vulnerability.

To reduce dependency:

Deploy sensitive workloads on on-premises infrastructure or hybrid cloud environments.

Prioritize regional data centers in politically aligned jurisdictions that offer greater legal protection from extraterritorial reach.

Adopt multi-cloud orchestration using platforms like Terraform and Kubernetes to enable cloud portability and resilience.

Why it matters: For example, hosting AI workloads on U.S.-based hyperscalers like AWS or Azure exposes enterprises to potential obligations under the U.S. CLOUD Act. Localized deployment reduces regulatory and operational fragility.

Data

Data is both a strategic asset and a legal minefield. Its collection, storage, and cross-border movement increasingly fall under national regulatory frameworks like GDPR, India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act, and China’s PIPL.

Recommended safeguards:

Use external key management systems (KMS/HSM) so encryption keys remain outside cloud vendor control.

Implement confidential computing (e.g., Intel SGX, AMD SEV) to protect sensitive data in-use, not just at rest or in transit.

Audit and document all cross-border data flows, establishing clear data lineage and regional processing mandates.

Why it matters: Organizations need to protect against both unauthorized access and legal overreach. Data breaches or subpoenas from foreign jurisdictions can trigger penalties, loss of customer trust, or business interruption.

AI Models and Foundational Models (LLMs)

There many AI models out there: some open, some closed and proprietary. In particular, the explosion of proprietary large language models have made the headlines due to their incredible training cost (hundreds of millions of dollars) and raise questions about dependency, license stability, and alignment with organizational values.

Finding the Right AI Model for the Job is not always easy: so I have created guide to help identify the type business problem you have and match it to the right AI model to solve it. 64 use cases across 23 industry domains mapped to 80 AI models.

The considerations below focus specifically on LLMs as they are driving the incredible hyper around AI adoption globally and the need for resources and compute.

Mitigation strategies include:

Adopting (partially) open-source LLMs like Mistral, LLaMA 3, Falcon, Qwen, DeepSeek or Yi.

Deploying models on your own GPU clusters or regional hosting partners for greater control.

Prioritizing in-house fine-tuning and model customization to build differentiated, organization-specific AI capabilities.

Mapping LLM vendor jurisdictions to understand legal exposure.

Why it matters: Access to proprietary models (like GPT-4 or Claude) may be revoked due to export controls, license changes, or political pressure. Open models, if maintained responsibly, offer continuity, customization, and sovereignty.

On a side note, I think it’s important to cut through the noise and go beyond the hyper about what LLMs can and cannot do today. You can read further here:

Applications and Interfaces

AI services often sit on top of foreign software stacks; SaaS, identity providers, productivity suites, that can themselves be points of control or vulnerability.

Recommended actions:

Transition to sovereign or open source enterprise stacks where feasible (e.g., Linux, Nextcloud, LibreOffice, Keycloak).

Develop custom internal applications using sovereign frameworks to control data flows and backend architecture.

Incorporate geopolitical clauses in procurement contracts, especially around cloud services, model APIs, and data access.

Diversify currency exposure in digital procurement to reduce risk from SWIFT cut-offs or US dollar volatility.

Ensure AI literacy among internal teams to reduce reliance on opaque external services and consultants.

Why it matters: Vendor lock-in at the application layer makes sudden substitution difficult. Building flexible, modular systems preserves business continuity in a volatile regulatory environment.

6. The First 90 Days: A Practical Roadmap To Start Decoupling

While sovereignty sounds like a long-term aspiration, concrete steps can begin immediately. The following 12-week roadmap allows companies to assess and reduce exposure progressively.

By the end of this sprint, organizations will not be fully sovereign, but they will have mapped their exposure, taken visible steps to mitigate risk, and built internal momentum for change.

7. From Risk to Strategic Advantage

The pursuit of AI sovereignty is not about decoupling from the global economy or rejecting innovation. It’s about insulation and realism: recognizing that control over digital infrastructure is now a determinant of geopolitical and corporate power and necessary to insulate the business against external volatility factors.

Organizations that embrace this complexity will gain:

Resilience to sanctions and regulatory fragmentation.

Stronger customer trust grounded in transparent data practices.

First-mover credibility in a market that is rapidly moving toward compliance-heavy AI governance.

Optionality: the ability to adapt, switch, and evolve as geopolitical conditions shift.

Sovereignty is not about building everything in-house. It’s about designing with strategic autonomy in mind. It is about knowing not just how your AI stack functions, but who can shut it down.

The Bottom Line: From Powerlessness to Preparedness

Sovereignty begins with awareness. It matures through action. And it is preserved through institutional memory.

Your organization does not need to become an infrastructure company. But it does need to stop outsourcing its destiny.

The question is no longer whether to address AI sovereignty, but how quickly and how seriously you do so.

Would you like to know more? Understand regulations and geopolitical risks you might be exposed to better? Or how is your current digital infrastructure at risk today? Just don’t know where to start?

Let’s start the conversation: just hit reply to this email or explore more at https://rebootup.com/

Thanks for reading!

Damien

This article was prepared based on the Technopolitics Webinar Series, a collaboration together Initiatik, a France-based Global Advisor on Risk Management & Cooperation Strategies, and RebootUp, a Singapore-based Digital Accelerator & Technology Advisory firm.